COVID-19 Vaccines: Where Are We Now?

“Global mass vaccination on this scale has not been attempted since the eradication of smallpox, which took 20 years to achieve.”

- Professor Katie Flanagan

In November Tasmania reached a significant milestone in the fight against COVID-19, with more than 80% of the population aged 16 and over fully vaccinated. By December, the goal was to reach a 90% vaccination rate in all Tasmanians over the age of 12.

The urgent need to develop safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines has been met with unprecedented speed and action from the global community. It is one of the greatest public health achievements in history.

But even at the current rate it could take years to vaccinate the world’s population. There is still much that researchers don’t fully understand about immunity to the new disease, and its emerging variants. But there is renewed hope for the journey forward.

In October, a Clinical Commentary Review co-authored by Launceston General Hospital Infectious Disease Specialist Katie Flanagan was published by Elsevier Inc, on behalf of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

‘SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: Where are we now?’ discusses the clinical trial data that led to rapid emergency use authorisation, along with the many challenges of the global vaccine roll-out. Researchers also commented on some of the key unanswered questions and the future directions for COVID-19 vaccine development and deployment.

Here are some of the highlights:

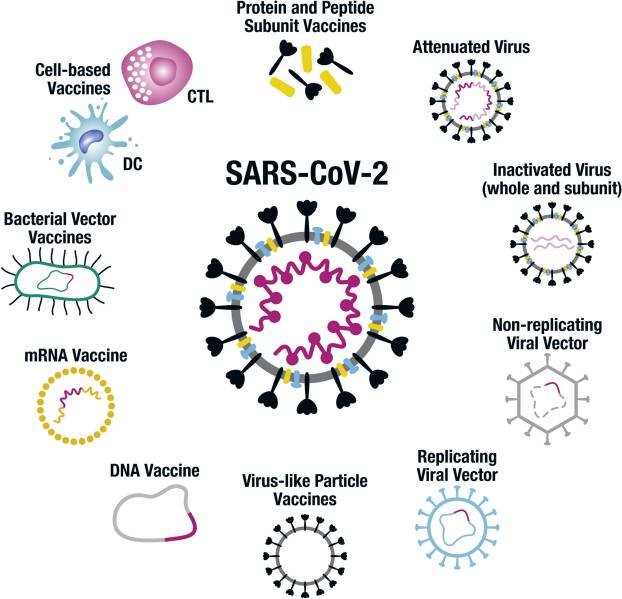

An illustration of the conventional and novel platform technologies being used to develop COVID-19 vaccines.

Where are we at?

As of July, 2021 there were 184 COVID-19 vaccine candidates in preclinical development and 105 in human clinical trials. A little over 12 months after the declaration of a pandemic by the World Health Organisation, the phase 3 efficacy results of a number of vaccines were published. Nineteen vaccines had regulatory approval (most preliminary and emergency use only) and more than 3 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been administered globally.

How did we get here so quickly?

According to the review, international regulatory bodies played a pivotal role in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic response through the oversight and facilitation of clinical studies which led to emergency use authorisation.

While a typical vaccine development can take up to 10-15 years, unprecedented collaboration and transparency between regulatory bodies, clinical investigators and industry led to a monumental shortening of this review cycle – without compromising long-standing standards for new vaccine development.

“Government pre-purchase contracts provided the important vaccine development and manufacturing incentives, whereas regularity bodies opened unprecedented lines of communication, progressing a model of rolling reviews to facilitate actionable data.”

Impact on transmission

Emerging real-world data shows impressive effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against symptomatic infection, hospitalisation and death from COVID-19.

A Scottish prospective study in 5.4 million people, of which just over 1.3 million had received their first dose, showed 88% protection from the AstraZeneca vaccine and 91% protection for the Pfizer vaccine against hospitalisation, 28 to 34 days after vaccination.

Further studies have also shown that COVID-19 vaccines reduce asymptomatic infection, and thus the likelihood of disease transmission. For example, two doses of Pfizer vaccine provide efficacy against asymptomatic infection of >85% in several studies.

Issues for global mass vaccination

Herd immunity is considered the cessation of sustained community transmission and protection of unvaccinated people, when vaccination rates are high enough. According to the review, mass vaccination, which has been pursued by countries such as Israel, may lead to herd immunity – with the required level of vaccination determined by the efficacy and effectiveness of the vaccine and the basic reproductive number of the infection, i.e, the number of infections that an infected case causes.

For SARS-CoV-2, to interrupt community transmission with a vaccine of 90% efficacy would require approximately 66% of the population to be vaccinated. However, the review notes this efficacy must be against all infections, rather than symptomatic infections only, which is a common endpoint in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials.

“A key determinant of herd immunity, therefore, is whether vaccines can stop transmission by preventing both symptomatic and asymptomatic infection.”

At-risk populations and future directions

Many elements are needed to ensure mass vaccination can be carried out – including: adequate vaccine supply, vaccinators and infrastructure, community outreach and a communication strategy to help combat vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine supply has been an issue for many countries. The review notes a growing concern around the inequities of international access to the vaccine, with the majority of vaccine doses available worldwide purchased by wealthier countries. As such, it is likely we will see hot spots of COVID-19 in the world for several years to come.

The review notes that a comprehensive strategy will be important to ensure vaccination and protection for the whole world. Immediate challenges include the logistics of manufacturing billions of vaccine doses, support to supply poorer nations, and the logistics of equitable distribution.

“Ongoing scrutiny for rare adverse event signals will be essential, in particular to ensure public confidence and vaccine uptake.”

Unanswered questions and conclusions

Variants of SARS-CoV-2 will continue to emerge, requiring close international monitoring and potential vaccination boosters. Currently, unanswered questions include the vaccine efficacy against disease transmission, the duration of protection and whether the use of mixed schedules of different vaccines can be used.

“The possibility of developing a pan-beta coronavirus vaccine that could protect against future emergent pandemic strains looks promising.”

The review notes there is still much to learn about the vaccine-induced immunity to COVID-19 and the next generation of vaccines are likely to be better than the first.